The Oldest Democracy in Asia at risk of grave DeclineTypes of Threat:

Background

Despite being classified in 2019 as an upper-middle income country by the World Bank, Sri Lanka, a country with over 21 million people and Asia’s oldest democracy, is facing one of its worse economic, political, and social crises in decades.

For months now, the country has been railed by nationwide peaceful protests as Sri Lanka’s foreign exchange reserves have run out, causing heavy shortages of food, fuel, medicine, and other supplies essential for the population’s survival. The healthcare system is on the brink of collapse as hospitals and medical centers are running out of essential stocks, non-urgent surgeries are being paused, and medicines are at a dangerous level of depletion. Families, children, and pregnant women are now struggling to afford nutritious food and life-saving services, including access to education, water, social protection, and health. As the unrest has rapidly escalated - aggravated by a series of ill-conceived economic reforms and austerity measures to curb the crisis - a worrying record of severe human rights violations, especially against those most vulnerable and marginalized, has already been documented by multiple organizations.

In this unprecedented context, President Gotabaya Rajapaksa declared a State of Emergency on 1 April, giving vast powers to the security forces after protesters tried to storm his house. Following weeks of raids on the street, his entire cabinet resigned en masse, and 42 government MPs decided to turn independent, leaving his party in the minority. In light of the increasing civilian demands and to quell social unrest, the second State of Emergency was issued on 9 May - followed by a third one on 17 July - where security forces were ordered to shoot those individuals deemed to be participating in violence. Notwithstanding the curfews, social media/press blockage, and attacks on demonstrators, Sri Lankans continued mass peaceful protests, calling for President Gotabaya Rajapaksa’s immediate resignation. The situation culminated with Mr. Rajapaksa stepping down and fleeing the country secretly while renouncing from abroad.

As the political crisis unfolded and exacerbated, on 20 July, the Sri Lankan Parliament elected six-time Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe as its new president. Sri Lankans, nonetheless, also opposed his elevation as the country’s top leader while accusing him of being an ally and shielding Rajapaksa and his family, who have ruled the island for years. The newly elected President had also been subjected to an independent investigation that identified him as allegedly responsible for the administration of “detention systems” in the region of Battilana that led to thousands of allegations of torture, enforced disappearances, and other human rights abuses at the end of the 1980s.

As one of his first measures to minimize the impact of the crisis, Wickremesinghe's government announced on 25 July restrictions on fuel imports for 12 months as the country faced a severe supply shortage. Schools were closed, and employees were urged to work from home to deal with the remaining petrol reserves, raising grave concerns as it can further impact children’s education and health which has already been disrupted and deteriorated for years due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (UNOHCHR) warned of a record high inflation, rising commodity prices, malnutrition, and food insecurity all over the country with catastrophic effects on vulnerable populations as numbers are expected to deteriorate in the coming months.

Issue

Emergency powers previously invoked in Sri Lanka have been used indiscriminately to justify atrocity crimes and curtail fundamental rights. According to the country’s law and emergency regulations, the president may override any law - except the Constitution - that might prove inconsistent or contrary. Moreover, certain fundamental rights enshrined in the Constitution can be subjected to restrictions in the interest of national security, including equal treatment before the law; freedom of assembly, association, movement, and cultural and religious expression; and procedural requirements in arrest and detention.

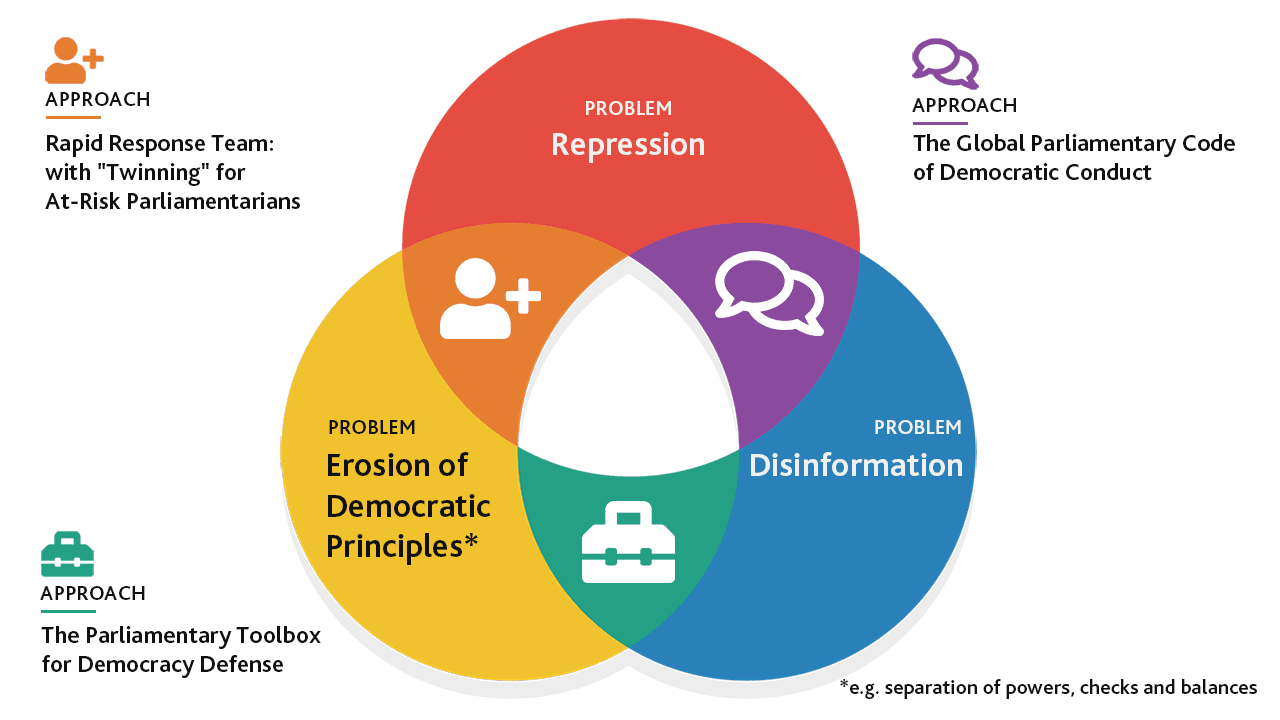

The rapid escalation and the emergency measures issued by the different governments giving broader authority to act independently to restore the order have, indeed, resulted in a wave of grave human rights violations contributing to a growing climate of fear and repression, as reported by Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch, and UN human rights experts. Social media platforms have been temporarily blocked to secure order in the country amid the curfew defied by Sri Lankans protesters demanding accountability. False rumors about incidents occurring throughout the country have rapidly spread, and politically motivated false information about the opposition and misinformation campaigns about the crises have also become prevalent in the past months.

Since the first State of Emergency was declared in April, those opposing the previous and new government have been tackled with excessive use of force, resulting in the detention of over 600 people for violating the curfew. Many arrested have claimed to be subjected to torture and ill-treatment and removed from their right to be produced before a magistrate. Although protests have been largely peaceful, with some sporadic acts of vandalism per some reports, the authorities have restricted the right to freedom of movement and assembly by using tear gas and shooting live ammunition.

Likewise, law enforcement authorities are not only forbidding legitimate political and freedom of expression but also criminalizing, detaining, and persecuting activists’ leaders, parliamentarians, and demonstrators, bringing against them disproportionate and excessive criminal charges for acts of civil disobedience. Since the unrest commenced in March, 41 homes of top ruling party politicians have been torched overnight despite curfews. Reports also suggested that over 200 people have been injured and eight people have been killed, including legislator Mr. Amarakeerthi Athukorala. Sri Lanka’s Attorney General directed the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) to arrest 22 people, including MPs Johnston Fernando, Sanath Nishantha, Sanjeewa Edirimanna, and Senior DIG Western Province Deshabandu Tennakoon, if sufficient evidence was found against them for inciting violence during the 9 May incidents.

Despite the multiple demands calling to secure order, focus on peaceful and democratic transition, and respect human rights, economic, social, political, and civil rights have continued to be curtailed. With the fuel crisis and power cuts, the island is also losing years of progress in sanitation, hygiene, nutrition, and maternaland child health. As of 23 July, 19 people have died in lines to get gas supplies. Moreover, the power shortages, lack of medicines, and appropriate equipment seriously threaten children and pregnant women’s opportunities to access appropriate health services, and the precarious conditions have undermined sexual and reproductive rights, including maternal health care, access to contraception, and other services to prevent and respond to gender-based violence.

PGA’s Perspective

Any hope for Sri Lanka’s recovery is intrinsically tied to the need for accountability and respect for human rights. Sri Lanka’s weakening of democratic institutions has affected its ability to tackle the crises and ensure the realization of economic, social, cultural, civil, and political rights for all citizens.

Parliamentarians for Global Action (PGA) urges President Ranil Wickremesinghe’s government to ensure that emergency measures that have been overly used to enable the military to detain people for up to one day without disclosing facts, to create new extreme sentences rules, to crack down on protests, and infringe on the exercise of fundamental human rights, are halted immediately. The government must refrain from using violence against demonstrators, journalists, and human rights defenders, and emergency measures cannot be used to silence, arbitrarily detain, torture, and/or disappear dissent.

Under international law, the use of force is a last resort, and the response to clashes must be proportionate.Moreover, even if States can derogate from certain obligations, they can only do it in times of an officially proclaimed State of Emergency that threatens the life of the nation and only to the extent strictly required by the exigencies of the situation. Neither the right to life nor the prohibition of torture (a jus cogens norms) can be limited under any circumstance. The guarantee of these, and other rights, are protected by international human rights instruments and are an essential part of any functioning democracy.

Additionally, PGA stresses that as a party to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), Sri Lanka must ensure that individuals thoroughly enjoy the rights to freedom of assembly, expression, and speech without fearing retaliation. The Act, No. 56 of 2007, giving effects to specific articles of the ICCPR and previously used to disproportionately target Tamil and Muslim communities, should be amended to stop the persecution of religious and ethnic monitories. In relation to the health crisis, under Sri Lanka’s responsibilities enshrined in the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR), the government has an immediate obligation to ensure the availability and accessibility of essential healthcare services and products to the population and take all the necessary measures to protect the rights to life and the highest attainable standard of health.

Following the allegations of torture, enforced disappearances, killings, and other serious human rights violations during the protests and over the last years, PGA calls on the government to ensure prompt and impartial investigations. Now that Mr. Rajapaksa no longer has sovereign immunity from prosecution, PGA calls States, where the law permits, to recourse to appropriate principles of jurisdiction – including universal jurisdiction – to investigate and prosecute him and other individuals - where appropriate - involved in the alleged commission of international crimes, including crimes against humanity committed during the long civil war. Since previous governments in the country have not been held accountable for mass abuses, avenues such as universal jurisdiction can play an essential role in international efforts to deliver justice and redress to victims and their families who have nowhere else to turn.

Impunity for past mass human rights violations is fueling the repetition of crimes in present days and may continue creating an incentive for new atrocities in the future. PGA calls all relevant organs of the International Community, including the High Commissioner of Human Rights, to take all necessary measures to re-start past processes aimed at bringing to justice the alleged perpetrators of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and, if applicable, genocide committed in Sri Lanka, especially those perpetrated in the first decade of this century. PGA calls upon all political parties that want to reinstate democracy, justice, and the Rule of Law in Sri Lanka, to commit to the legal principle of “never again” and include the ratification of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court in their programmatic platform so that there is a credible and legislative guarantee of non-repetition of the mass-atrocities of the past.

Unfortunately, the concentration of powers in Sri Lanka, coupled with censorship, lack of access to fundamental rights, and a militarized response to situations such as the COVID-19 or the ongoing crisis, can have catastrophic effects on its democracy. These trends may likewise reinforce a climate of authoritarianism that can result in other serious human rights violations - especially against marginalized groups - and breaches of the constitutional order. As Sri Lanka is being listed by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) on the Hunger Hotspot list of States who will likely run out of food during the expected global food crisis, and as we face a humanitarian emergency, we urge the government to tackle the situation effectively and promptly in order to protect individuals’ fundamental human rights. Authorities must also guarantee that immediate assistance is provided to those most vulnerable.