Gross Negligence Of Brazil’s Indigenous Population During The Covid-19 Pandemic May Amount To GenocideTypes of Threat:

Issue

On 26 February 2020, the Ministry of Health of Brazil confirmed the first novel coronavirus case in the country. To date, Brazil has the second-worst world outbreak of the coronavirus with over 3 million reported cases and 101,049 deaths, putting an additional strain on a faulty public healthcare system. The rapid spread of the virus is attributed to the incoherence and lack of concerted efforts by federal government officials to establish and implement policies that consider the seriousness of the illness and its impact on vulnerable populations, including indigenous persons in the Amazon rainforest and poor Black communities. Indeed, according to the Articulação dos Povos Indígenas do Brasil (Articulation of Indigenous Peoples of Brazil, APIB), 23.453 indigenous persons have been diagnosed with Covid-19 and 652 individuals have died.

Indigenous people face a multitude of challenges, from poor access to essential sanitation services to being treated by ill-equipped medical professionals. The COVID-19 pandemic has worsened this dire picture: indigenous people die at a higher rate than the rest of the Brazilian population as they cannot even access key preventive measures such as clean water and soap.

In May 2020, the traditional Councils of the Guarani and Kaiowá People, Aty Guasu (General Assembly of the Guarani & Kaiowá People), Kuñangue Aty Guasu (Great Assembly of Guarani & Kaiowá Women), RAJ (Guarani & Kaiowá Youth Movement), Aty Jeroky Guasu (General Assembly of Guarani & Kaiowá Shamans), released a statement of solidarity in the face of a situation that threatens the survival of their people. Despite this plea for survival, over 1,000 workers working with the federal Special Indian Health Service of the Ministry of Health (SESAI) have tested positive for coronavirus.

As these workers lack adequate protective gear and access to tests, they may have endangered the already vulnerable indigenous communities. On 5 June, a team of health workers had been accused in a report by Brazil’s Attorney General of “flagrant negligence” of pertinent safety standards. The report had also raised concerns that infected workers may have spread the virus to other villages. A different team had been accused of “flagrant disregard of the epidemiological risk” for entering the Javari reserve without following quarantine protocols, to care for vulnerable Korubo tribespeople. Moreover, the report cites the “patent deterioration” of the enforcement capacity of the National Indian Foundation (FUNAI) to establish and implement policies to defend the boundaries of indigenous lands. The Foundation is a government body charged with the protection of lands inhabited and used by indigenous tribes and the prevention of invasions of said lands by outsiders.

Current protocols outlined in SESAI COVID-19 Contingency Plans do not conform to World Health Organization Guidelines and Recommendations. Consequently, they are grossly negligent and violate numerous domestic and international legal instruments such as the 1988 Constitution, ILO Convention 169, and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

Some commentators have qualified the intentional negligence of the Brazilian government as genocidal. Indeed, on 8 July, President Bolsonaro had vetoed some parts of an emergency bill that would ensure access to drinking water, free distribution of hygiene products, and the distribution of cleaning and disinfection materials to indigenous communities. He vetoed a proposal ensuring mandatory emergency funds for the healthcare of indigenous peoples and argued that legislating mandatory expenditures does not “account for the respective budgetary and financial impact, which would be unconstitutional.”

Government health-care workers are not the only vector of infection into protected indigenous territories. Illegal mineral prospectors are also responsible for propagating the novel coronavirus. According to the Brazil National Institute for Space Research, “[d]eforestation rates in the Brazilian Amazon are up nearly 60 percent over last year, […] with enforcement efforts crippled by the lockdown and official edicts that have cut back on protections for the environment and indigenous populations.” Rights activists have raised concerns about the increase of illegal mining and logging on indigenous lands since President Bolsonaro came to power.

On 5 August, the Supreme Court of Brazil affirmed an earlier decision taken on 8 July which stated that the Bolsonaro government must adopt and enforce measures to stop the propagation of the novel coronavirus to indigenous communities. The decision however did not address the main demand of indigenous groups to set a deadline for miners, developers, and the military to leave indigenous territories. The same day, a prominent indigenous leader Chief Aritana Yawalapiti of the Upper Xingu territory died of the virus. Chief Yawalapiti was admitted in July while suffering from acute breathing issues. As it was the case with Chief Yawalapiti, every time an indigenous leader dies, it is a devastating loss as they are living histories of their culture. According to Tiago Moreira dos Santos, an anthropologist with Instituto Socioambiental, “[t]hey are the guardians of a culture. We’re talking not only about myths and stories but also about language, memory, and knowledge that are fundamental to the existence of a people.”

Fundamental human rights of Indigenous Peoples should be upheld worldwide, especially in Brazil where the government is intentionally implementing policies that are detrimental to their physical and psychological integrity. Indigenous communities are the guardians of the most biodiverse region and largest rainforest on planet Earth and if we want a better future, we must protect indigenous peoples and their fundamental rights. The European Union has a role to play in this endeavor, by ensuring that its trade agreements include clauses on the respect of fundamental human rights and international environmental standards and sustainability.Hon. Petra Bayr, MP (Austria)

PGA Executive Committee Member

Chairperson of the Committee on Equality and Non-Discrimination, Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe

9 August marked the International Day of the World’s Indigenous Peoples. The United Nations commemorated this day with a call: “Especially now, they need us. Especially now, we need the traditional knowledge, voices and wisdom of indigenous peoples.”

Context

The health crisis unfolded against a background of political and economic turmoil that exacerbated its devastating effects. On numerous public occasions, President Bolsonaro downplayed the COVID-19 as a “little flu”, which he later announced having contracted. Under his tenure, the response of the Brazilian government has been inadequate and misguided. Although the federal government approved in April 2020 an emergency aid package for informal workers, the modest amount has done little to ease the financial burden on the most vulnerable groups of the Brazilian society.

While most countries worldwide imposed confinement measures in early 2020, President Bolsonaro has been railing against quarantine measures and urging people to go back to work. Social distancing measures are perceived by the Executive as a threat to the economy, which would in turn lead to “misery, hunger, and chaos”. Despite the President’s call to continue with business as usual, State governors and city mayors have followed health and public safety recommendations, including lockdowns. The President has called state governors who issued lockdowns “job-killers”.

Mr. Joao Doria, Governor of the State of Sao Paulo, said that “[t]here is no leadership. President Jair Bolsonaro is not leading Brazil at such a serious and difficult time” and that the president is “acting as an army captain who has no knowledge, no scientific experience in health or public health, who works according to what he thinks, on assumptions, and personal desires on a subject very serious because it has to do with people’s lives”. He also explained that “no governor will accept President Jair Bolsonaro’s recommendation not to isolate or interrupt the isolation. All governors understand that the measure is necessary and that the coronavirus crisis is serious.”

In summary, since his swearing-in ceremony on 1 January 2019, President Bolsonaro has fully embraced a far-right populist rhetoric and engaged in a disinformation campaign, specifically on COVID-19, which has yielded dramatic consequences for his country. For instance, President Bolsonaro endorsed hydroxychloroquine as a cure for Covid-19 although the scientific community has rejected such findings and warned about risks associated with the anti-malaria drug. The repeated positive messages of the President on the drug have caused issues to healthcare professionals in Brazil. A survey conducted by the São Paulo Medical Association with approximately 2,000 health professionals found nearly 50% of them have been pressured by COVID-19 patients or family members to prescribe it. The Brazilian Society of Infectious Diseases publicly opposed the use of chloroquine and its head reportedly received an online death threat.

The US has donated two million doses of hydroxychloroquine to Brazil, which has been mostly untouched. In May, a judge ordered Facebook to block 12 accounts of Bolsonaro allies and Twitter to block 12 accounts. The groups were accused of spreading fake news against judges. The Supreme Court of Brazil, in late July, fined Facebook the amount of 1.92m reais ($368,000) for refusing to block worldwide access to the disputed accounts. Facebook only agreed to block access to accounts from Brazil. The Supreme Court further fined Facebook 100,000 reais each day the company failed to comply.

In the last 2018 presidential elections, the then-presidential candidate Bolsonaro was marred in a scandal in which mass messaging was sent through WhatsApp spreading false content aiming to attack his opponent . The Supreme Electoral Court itself was also targeted by false information online and recognized the difficulty to deal with the overwhelming wave of fake news in the country. Disinformation campaigns carried-out at the highest levels of the Brazilian state have undermined democratic institutions and principles and weakened the respect for fundamental human rights and civil and political rights.

In an attempt to address the spread of false information, a ‘fake news’ bill 2630/2020 was introduced in the Senate on 13 May 2020. In late June, the Brazilian Upper House passed “The Brazilian Internet Freedom, Responsibility and Transparency Act”. The vague and overbroad provisions of the law are dangerous as they allow, inter alia, for infringements on the freedom of expression and raise serious privacy concerns. It has been sent to the Lower House of Congress for review and approval.

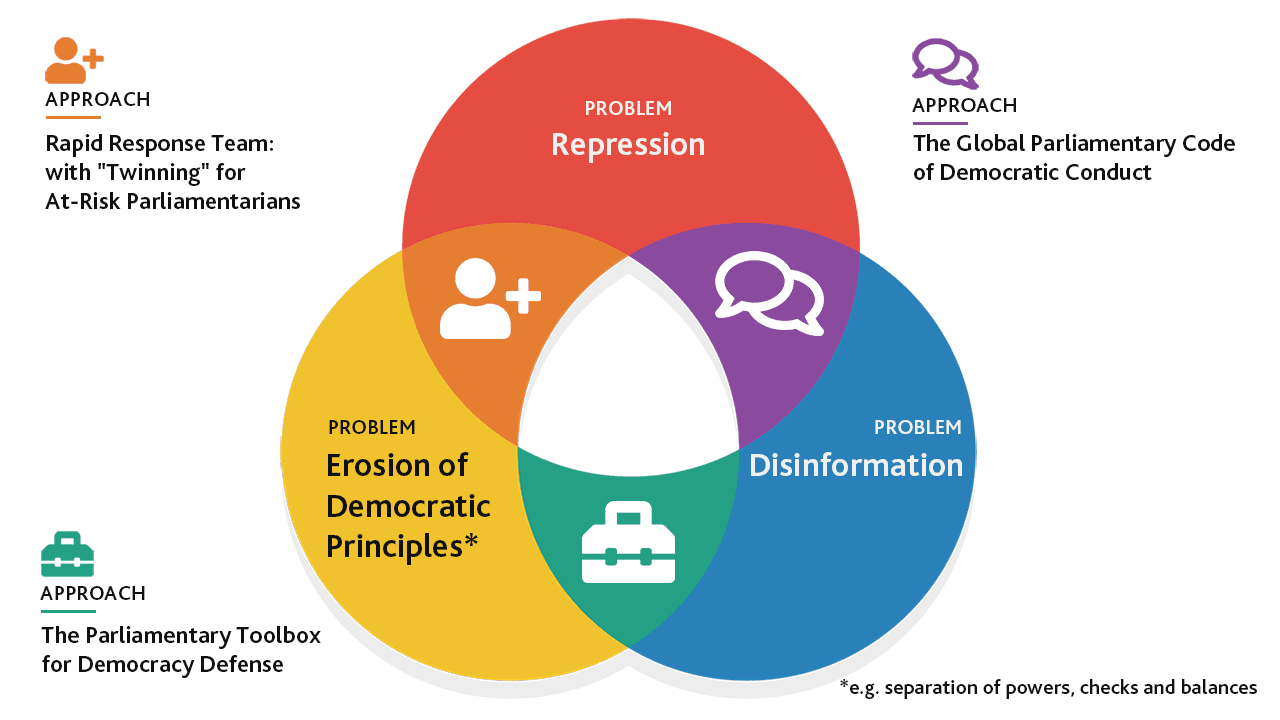

PGA's Perspective

Countries worldwide are grappling with the COVID-19 pandemic and its consequences on health, the economy, and the social fabric. More than ever, it is paramount to strengthen democratic institutions at such a delicate historical juncture.

After the military dictatorship in Brazil from 1964 to 1985, the country’s new Constitution became law in 1989 establishing the Federative Republic of Brazil. Brazilians since then have enjoyed full democracy. In 2002, the election of Lula da Silva was perceived by many observers as the culmination of the return to democracy in the country. Brazil was full of promise until corruption scandals marred the presidency and the mandates of high government officials. A perfect storm sparked a crisis of confidence in democratic institutions and profound dissatisfaction of Brazilians in their government for several reasons, including the economic recession and the slowly increasing crime rate. Consequently, a shift happened in 2018 when a populist retired military captain and long-standing, albeit “obscure” legislator, who openly made the apology of the military dictatorship, was elected as the 38th president of Brazil. From his campaigning days, President Bolsonaro demonstrated disregard for fundamental democratic principles such as popular sovereignty, the separation of powers, checks and balances and respect for fundamental human rights and the rule of law. The COVID-19 health crisis further revealed and entrenched societal inequalities; vulnerable populations such as the Indigenous Peoples are left suffering and exposed to a greater death rate from the disease.