By Sir Ronald Sanders, Ambassador of Antigua and Barbuda to the United States and the Organisation of American States

A regressive 19th century law, that is a legacy of British rule, continues to exist in 10 of the 12 independent Commonwealth Caribbean states.

The law, inspired by the 1553 Buggery Act in England, was imposed on all British colonies by the colonial government in Britain in 1861. It effectively outlawed homosexuality.

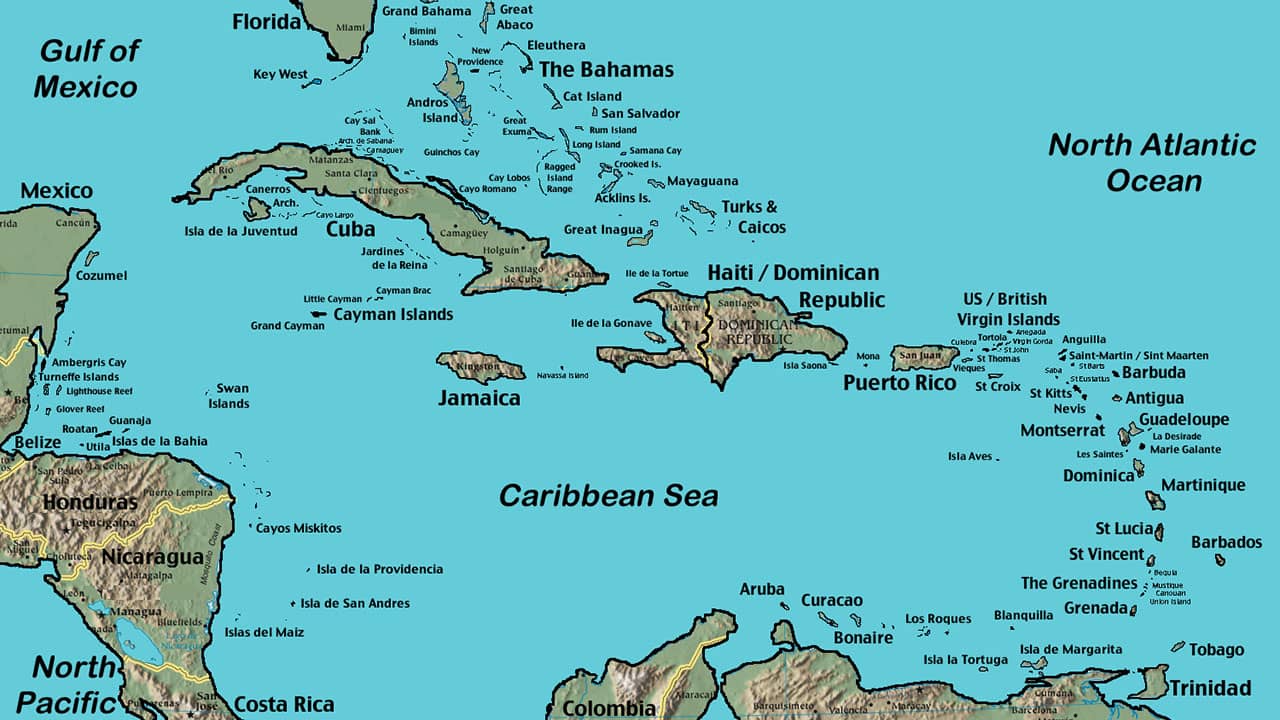

The two independent Commonwealth Caribbean countries that have done away with this archaic law, which, it should be emphasised, was not enacted by Caribbean legislators, are The Bahamas and Belize. The law also does not exist in Haiti and Suriname which, together with the 12 independent Commonwealth countries, comprise the Caribbean Community (CARICOM).

In one of the 10 countries, Trinidad and Tobago, a High Court judgement ruled that sections of the existing law, which criminalize buggery between consenting adults, “are unconstitutional and should be struck down”. So, there has been action by the judiciary to reject the consequences on the Trinidad and Tobago society of a law imposed by colonial England one hundred and fifty-seven years ago.

The law was not imposed by Britain in 1861 because there was a demand for it within its many colonies at the time. It was reportedly imposed to protect British soldiers and colonial administrators from “corruption” out of a fear that these men sent far from home (and their women) would turn to homosexuality.

Of course, the law has long since been discarded within Britain itself. Today, homosexual men and women play leading and public roles in every aspect of British society, including its government.

Other former colonies of Britain have also repealed this archaic law. Among these countries are Australia, Canada, South Africa, New Zealand, and most recently India.

The discarding of laws that discriminated against citizens based on their sexual orientation has unleashed economic activity and productivity in all these countries. People who lived lives of fear, closeted from the society and afraid to participate to the full extent of their talents and creativity, are now freely contributing to government, the arts, and the advancement of their countries’ economies in unprecedented ways.

Holding back any society on the basis of any form of discrimination – gender, race, religion, and sexuality – stunts it, depriving it of talent, expertise, and productivity that would otherwise contribute to its growth and development.

Of the over 200 nations in the world, only 70 retain laws that discriminate against its citizens based on their sexuality. Of those 70 countries, 35 are in the Commonwealth – all of them retaining the law imposed upon them by colonial England. The majority of these Commonwealth countries are in Africa (13), followed by the Caribbean (10) the Asian region (6), and the Pacific (6).

This “Commonwealth” problem had been identified by the Eminent Persons Group (EPG) on which I served as a member and Rapporteur between 2010 and 2011. In our report, “A Commonwealth of the People: Time for Urgent Reform” submitted to the 2011 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in Australia, we recommended that: “Heads of Government should take steps to encourage the repeal of discriminatory laws that impede the effective response of Commonwealth countries to the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and commit to programmes of education that would help a process of repeal of such laws”.

The EPG cast the repeal of these discriminatory laws in the context of curbing the spread of HIV/AIDS because Commonwealth countries comprised over 30 per cent of the world’s population and over 60 per cent of people living with HIV resided in them. We recognised that discriminatory laws made homosexuals outlaws and, therefore, deterred persons suffering with HIV from seeking medical attention, lest they be imprisoned. The human carnage was sizeable; it was also needless.

There was much discussion within the EPG about whether to include this recommendation, not because we had any reservation about its rightness, but because a few of us feared – me included – that some leaders would be motivated by their fear of repealing the buggery law to discard the entire report and, with it, solid recommendations for urgent reform of a withering Commonwealth.

Eventually, the recommendation was included because of the persuasive arguments of two members of the EPG – Michael Kirby, a former Justice of the High Court of Australia, and Asma Jahangir (now deceased), a Pakistani human rights lawyer who served as the United Nations Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion or Belief.

Their argument was simple but compelling: No person should be denied the right to live their lives in equality with other citizens because of who they are in terms of race, political persuasion, religious beliefs, gender or sexual orientation. Kirby acknowledged that the path to achieve this objective is not easy, but he reminded me and other members of the group that, when we fought against the wrongs of apartheid in Southern Africa, we knew that we were arrayed against mighty forces of bigotry, racism, and political interest; yet we fought because we knew that what existed was wrong.

The discriminatory laws against homosexuality, and other forms of sexual behaviour by consenting adults, continue to be defended by a few churches. In the Caribbean and Africa, these churches are predominantly foreign and dogmatic, and lawmakers are made hesitant to repeal these laws in the face of their assertive influence on local populations.

But, other churches offer progressive views. For instance, the General Convention of the Episcopal Church has declared that “homosexual persons are children of God who have a full and equal claim with all other persons upon the love, acceptance, and pastoral concern and care of the Church”, and Pope Francis has observed, “If someone is gay and searches for the Lord, who am I to judge?”

The ten Commonwealth Caribbean countries are burdened by colonial left-overs, including ancient and imposed anti-homosexual laws; it is time for them to move on and join the progressive nations of the world by freeing their citizens in equality.

This article originally appeared on Sir Ronald Sanders’ personal website and is republished here with his permission.