Is the International Community Abandoning the Fight Against Impunity?

Debate organized by the International Center for Transitional Justice

Intervention by David Donat Cattin (Ph.D., Law),

Secretary-General, Parliamentarians for Global Action; Adjunct Professor of International Law, NYU Center for Global Affairs

I respectfully disagree with the vision of victor's justice proposed by Prof. Ignatieff.

2014 has been the darkest year for the International Community since the end of mass-atrocities in Rwanda (1994 – approx. 800,000 civilian casualties) and the former Yugoslavia (1995 – over 200,000 casualties). The emergence of a genocidal regime – the self-described ’Islamic State’/ISIL/ISIS – is the major indicator of the escalation of violence in Syria (approx. 200,000 casualties), regarding which in May 2014 Russia and China vetoed a Resolution backed by 13 States to refer the situation in Syria to the International Criminal Court (ICC). This was a much darker day for international justice in 2014 than the decision of the ICC Prosecutor to halt her proceedings in the case regarding the President of Kenya for his alleged individual criminal responsibility in crimes against humanity that might have taken place in the course of the post-electoral violence in 2007-08 (approx. 1,300 casualties).

The promise of total impunity given to the Assad regime by its powerful allies dates back to 2011, when the regime began its policy of systematic and massive crimes against humanity to destroy early protests and demonstrations that eventually became an armed insurgency. The Syrian conflict(s) accounted for more civilian victims than any other armed conflict that has occurred on our planet since international criminal justice became a “system” on 17 July, 1998, the date of the adoption of the Rome Statute, and 1 July, 2002, date of its entry into force and progressive operationalization of the ICC. The Russian patronage of the Syrian regime created a total “impunity-zone” that illustrates why the fight against impunity remains a necessary and relevant ingredient to prevent and repress mass-atrocity crimes. I will now make a brief, summary review of what happened in the world since mid-2002, when the Rome Statute system created a permanent forum to bring to justice alleged perpetrators of international crimes should relevant States prove unable or, as in most of cases, unwilling to exercise their sovereign jurisdiction in criminal matters.

First, between 2002 and early 2006, the United States started to lobby against the ICC with a global campaign during the first Bush Administration. This anti-Campaign for the Rome Statute of the ICC began to retreat when, on a 12 March 2006 visit to Bolivia, Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice stated that, “we are shooting ourselves in the foot”[1]: In fact, several States who refused to sign Bilateral Non Surrender Agreements with the US and received cuts in military and economic aid had moved to become partners of China, Venezuela and other States in these strategic areas of cooperation. As the history of the United States constitutional values tells us, there are principles that are more important than others, and the time had come to put an end to impunity for most serious crimes of concern to the International Community as a whole, at least as a matter of principle. Small and medium powers, including Kenya, were ready to pay a price and stand for this principle.

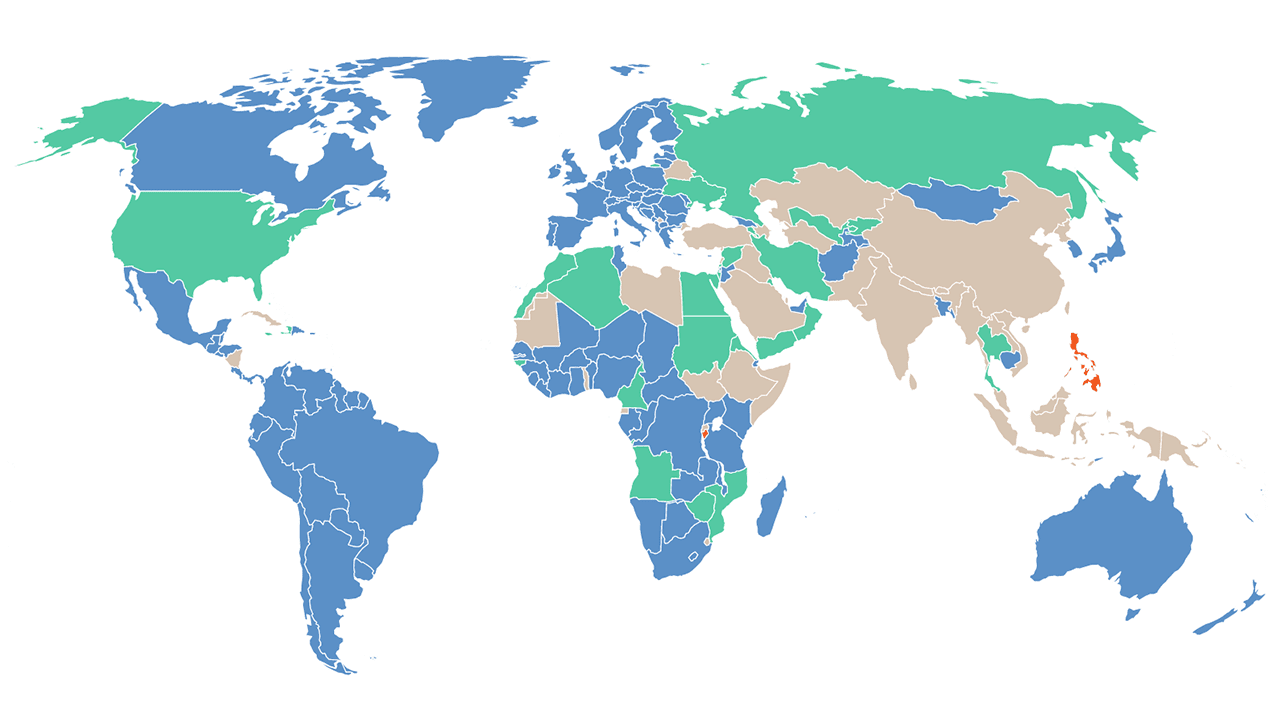

Second, 122 States plus Palestine joined the Rome Statute system. Did they succeed in putting an end to impunity? Not yet, of course, because there is no national criminal justice system that can claim to have attained such a result vis-à-vis ordinary crimes and offenses after centuries of operations of National Courts. But all these States agreed, and continue to agree, that enough is enough: impunity for mass atrocities shall never be tolerated. Those commitments send strong signals worldwide that the commission of those crimes should not go unpunished and give hope to victims that justice can be done.

Third, can armed conflicts and atrocities that occurred since the entry into force of the Rome Statute, apart from Syria, be compared with mass-atrocities of the 1990s (Rwanda, Bosnia and the rest of the former Yugoslavia, Sierra Leone and Liberia, Burundi and Zaire/DR Congo, to name a few) as well as of previous decades in the which International Law had been frozen by the Cold War (e.g. Cambodia, with the 2 million victims of Pol-Pot’s killing fields)? In most ICC-scenarios, primarily war crimes occurred and the level of victimization has been in the thousands (Central African Republic, Cote d’Ivoire, Mali, Kenya and Libya), not in the region of the hundreds of thousands of the 1990s, or the millions of the Cold War and the World Wars. There are not credible and verifiable statistics relating to the situation in DR Congo, but certain figures of humanitarian agencies appear different from the ones provided by certain official sources. The atrocities attributed to the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) progressively declined since the entry into force of the Rome Statute by Uganda, the ICC investigation, the Juba peace-talks and the strategy of this criminal group to re-position itself in neighboring countries. Yet, Sudan has been for many years the black hole of the system, with atrocities in Darfur causing very high levels of victimization, regarding which statistics are contradictory. But the worst mass-atrocities of the last fifteen years occurred outside the Rome Statute system, in territories where leaders assumed to be protected by powerful sponsors or defiant neighbors (as in the case of Presidents Bashir and Kenyatta vis-à-vis South Sudan). The mass-atrocities in Syria, which tragically spilled-over into Iraq and northern Lebanon due to ISIL/ISIS and similar groups since June 2014, occurred in a total impunity zone guaranteed by two Permanent Members of the UN Security Council, namely Russia backed by China.

Boko Haram is a different kind of phenomenon, which developed due to a number of root causes that should have been addressed in a much more effective and efficient way, under the Rule of Law and not violent revenge, by the largest and most powerful African state. Nigeria has so far failed in bringing to justice the brutal perpetrators of widespread and systematic attacks directed against its own civilians. The apparent inertia of the ICC Prosecutor on the Boko Haram situation might, at first sight, be difficult to comprehend, given the jurisdiction that the Court has on Nigeria and the visible ‘self-incriminating’ conduct by the Boko Haram commander who vindicated the enslavement of hundreds of girls forcefully abducted from school and other acts of mass murder, mutilation and inhumanity. But the ICC Prosecutor may decide to proceed with confidential investigations and sealed charges against powerful accused who can escalate their level of violence against victims, witnesses and potential witnesses if allegations against them are made public (Article 68.1 of the Rome Statute peremptorily obliges all organs of the Court to protect their safety, security, privacy and well-being). In addition, the OTP has clearly stated on several occasions that it is monitoring the situation in Nigeria, expressing concern and reminding all parties implicated in armed violence of the jurisdiction of the Court over Rome Statute crimes allegedly committed in Nigeria[2].

All these considerations help us to understand the impact of the ICC since its creation. Indeed, according to some studies[3], its existence and the threat of activation of its jurisdiction in certain conflict zones might have led to reduced violence against civilians. Other research[4] highlighted that the opening of an investigation by the ICC in a given country has increased the number of domestic prosecutions for low-level state agents in that country due to relevant actors’ opportunity to mobilize in support of justice and legislative reform to fight impunity as, for example, in the case of the DR Congo or currently in the Central African Republic with the soon-to-be ‘Special Criminal Court’[5]. Those investigations, prosecutions and internal mechanisms are complementary to ICC efforts and contribute to form the Rome Statute system of accountability for the most serious crimes of international concern.

The ICC and the Rome Statute system have not been established to prosecute the losers after the end of an armed conflict. The ICC Prosecutor is not allowed to select situations and cases on the basis of a criteria of convenience to serve the interests of those most powerful and strong. The Rome Statute is a binding treaty that, under its Article 21, creates for the first time in the history of an international jurisdiction a hierarchy of sources of law, which is underpinning the notion of the Rule of Law, based on certainty, predictability and equality of all before the law. The victor and the powerful must be treated like the loser and the weak, otherwise the ICC would operate outside the Rule of Law and its own principle of legality. The institutional framework of the Court, ensuring independence and impartiality of its organs, and the powers of the Prosecutor, who can initiate investigations proprio motu (Article 15) on the basis of information received on crimes falling under the Court’s jurisdiction, demonstrate that the ICC is not a state-driven institution and that International Criminal Law applies not only “when in the interest of powerful states”.

Even if mass-atrocity crimes are back on the scene of a disgraced world order after the annus horribilis 2014, should we give up the fight for an effective and fair application of the law contained in the Rome Statute? The answer is no, we should continue to struggle for ‘peace through the law’, as Hans Kelsen indicated to us after the end of World War II. After all, if the Rule of Law is good for us, who live in privileged communities in the United States or Europe, why shouldn’t the same standards apply to our fellow human beings who live in certain parts of Africa, the Middle East or Asia affected by armed conflict or widespread repression? Just 40 years before the adoption of the Rome Statute of the ICC in 1998, the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 contained an international standard that provides us with the constitutional basis for the Rule of Law in a Rules-Based International Order, namely, that “all humans are born free and equal in dignity and rights”. If we do not give up, we will prevail, as long as we are consistent in fighting impunity for the gross and systematic violations of our common, shared human dignity.

[1] U.S. Rethinks Its Cutoff of Military Aid to Latin American Nations - March 12, 2006. For the first time, a senior US Cabinet Member, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice, opened the door for reconsidering the US anti-ICC policies in order to have better relations with Latin America. Due to the importance of this update, the entire launch of the news by United Press International (UPI) is hereby reproduced: U.S. MAY RECONSIDER AID TO CHILE, BOLIVIA, SANTIAGO, Chile - UPI, March 12, 2006. U.S. officials may look for ways to resume military aid to Latin American nations who failed to exempt U.S. citizens from International Criminal Court.

Secretary of State Condoleeza Rice, traveling in Chile, told reporters that eliminating or reducing military assistance to countries like Chile and Bolivia that are seeking to combat terrorism or drug trafficking is "sort of the same as shooting ourselves in the foot," The New York Times reported.

A law enacted by Congress required the cutoff of military aid to countries that did not exempt U.S. citizens from being brought before the court. At least 30 countries have declined to enact an exemption, including 12 in Latin America and the Caribbean, the newspaper said. The law allows U.S. President George Bush to waive the cut off of military assistance, but State Department officials said the administration was concerned that if some waivers were granted, other countries would demand them as well, the Times said.”

[2] http://www.icc-cpi.int/en_menus/icc/press%20and%20media/press%20releases/Pages/otp-stat-20-01-2015.aspx

[3] Beth Ann Simmons and Allison Danner. 2010. Credible commitments and the International Criminal Court. International Organization 64(2): 225-256: http://dash.harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/9938752/Simmons_Credible.pdf?sequence=1 and Jo Hyeran, and Simmons, Beth Ann. 2014. Can the international Criminal Court Deter Atrocity: http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2552820

[4] Dancy Geoff, and Florencia Montal. 2015. Unintended Positive Complementarity: Why ICC Investigations increase domestic Human Rights Prosecutions.

[5] PGA has been raising the necessity to create such mechanisms in the DRC with the Mixed Chambers and recently in the Central African Republic www.pgaction.org/news/car-special-court.html and www.pgaction.org/news/pga-welcomes-the-opening-second-investigation-in-car.html .